Yasujiro Ozu

- Leo Wong

- Joined: Sun Dec 19, 2010 2:17 pm

- Location: Albany NY

- Contact:

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

Saw Todas again and found myself enjoying it, though still not as much as some other Ozus.

- ambrose

- Joined: Wed Sep 08, 2010 2:16 pm

- Location: Durham United-kingdom

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

The conclusion of Tokyo Story was an obvious corrective as regards the overwhelmingly sentimental conclusion of Make way for Tomorrow. The orgy of self-recrimination between the siblings that marred the end of Make way for Tomorrow is conspicuous by its absence in Tokyo Story! In fact the total absence of self reflection exhibited by Sugimura Haruko's character is quite bracing!Michael Kerpan wrote:Kogo Noda (co-screen writer of Tokyo Story) was also familiar with McCarey's film -- but I'd say Tokyo Story is sort of a rejoinder to Make Way (and maybe the earlier Todas).

- movielocke

- Joined: Fri Jan 18, 2008 12:44 am

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

edit: doh, somehow my eyes scanned over An Inn at Tokyo and That Night's Wife. nevermind, probably can't fit everything silent on a five disc set. :-p

so I thought about it some more, and I think Criterion could release the remainder of the Silent Ozu films on a single five disc set, including fragments, without really pushing disc space requirements very hard (though the set would require dual layer discs, most likely):

Disc1: Days of Youth

Disc2: Fighting Friends (short), I graduated, but (fragments), A Straightforward Boy (mostly extant short), I Flunked, But

Disc3: Walk Cheerfully, The Lady and the Beard

Disc4: Where Now are the Dreams of Youth?, A Mother Should Be Loved (longest total runtime of all these discs, at 185 minutes)

Disc5: Dragnet Girl, Woman of Tokyo, Kagamijishi

A Ozu Gangsters eclipse set might be more like:

Disc 1: Walk Cheerfully

Disc 2: That Night's Wife

Disc 3: The Lady and the Beard, Woman of Tokyo

Disc 4: Dragnet Girl

so I thought about it some more, and I think Criterion could release the remainder of the Silent Ozu films on a single five disc set, including fragments, without really pushing disc space requirements very hard (though the set would require dual layer discs, most likely):

Disc1: Days of Youth

Disc2: Fighting Friends (short), I graduated, but (fragments), A Straightforward Boy (mostly extant short), I Flunked, But

Disc3: Walk Cheerfully, The Lady and the Beard

Disc4: Where Now are the Dreams of Youth?, A Mother Should Be Loved (longest total runtime of all these discs, at 185 minutes)

Disc5: Dragnet Girl, Woman of Tokyo, Kagamijishi

A Ozu Gangsters eclipse set might be more like:

Disc 1: Walk Cheerfully

Disc 2: That Night's Wife

Disc 3: The Lady and the Beard, Woman of Tokyo

Disc 4: Dragnet Girl

- reno dakota

- Joined: Mon Mar 17, 2008 11:30 am

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

Kagamijishi is not a silent, so that would clear some space (though not much) on your Disc5.movielocke wrote: so I thought about it some more, and I think Criterion could release the remainder of the Silent Ozu films on a single five disc set, including fragments, without really pushing disc space requirements very hard (though the set would require dual layer discs, most likely):

Disc5: Dragnet Girl, Woman of Tokyo, Kagamijishi

- movielocke

- Joined: Fri Jan 18, 2008 12:44 am

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

yeah, but it's short, and it's a documentary, not a feature fiction film, so it is an oddity that seems to fit more as an eclipse title rather than anywhere else, though I suppose it might make a good special feature on another ozu mainline release. Or, if we're really concerned that it violates the Silent Ozu name, call the set Early Ozu to counterpoint the Late Ozu set. :-preno dakota wrote:Kagamijishi is not a silent, so that would clear some space (though not much) on your Disc5.movielocke wrote:so I thought about it some more, and I think Criterion could release the remainder of the Silent Ozu films on a single five disc set, including fragments, without really pushing disc space requirements very hard (though the set would require dual layer discs, most likely):

Disc5: Dragnet Girl, Woman of Tokyo, Kagamijishi

Another possibility would be to drop the fragments, shorts, and Kagamijishi and do this (chronologically):

1. Days of Youth, I Flunked But

2. Walk Cheerfully, That Night's Wife

3. The Lady and the Beard, Where Now are Dreams of Youth?

4. Dragnet Girl, A Woman of Tokyo

5. A mother should be Loved, an Inn at Tokyo

The part I can't quite imagine in such a set would be the eclipse slip cover, I don't think you could fit 10-12 lines necessary to list all those titles, given the eclipse format, the most lines of titles so far is on the Malle set.

Also, another reason this is unlikely, and just a mere pipe dream, is that the longest double feature of the Naruse set is 125 minutes TRT, probably allowing them to use single layer discs, the shortest of the above ozu double features would be 147 minutes and the longest would be 185 minutes both of which would require dual layer discs.

- whaleallright

- Joined: Sun Sep 25, 2005 12:56 am

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

A smaller set could focus on Ozu's college comedies. Actually it'd be neat to have a set devoted to 1920s–30s Japanese college comedies, in general -- a robust genre.

- Michael Kerpan

- Spelling Bee Champeen

- Joined: Wed Nov 03, 2004 1:20 pm

- Location: New England

- Contact:

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

What would this have (other than Ozu's few remaining films of this sort? I can only think of a couple of Shimizu films -- like Boss's Son Goes to College and Star Athlete (which is a very different sort of film from the others).jonah.77 wrote:A smaller set could focus on Ozu's college comedies. Actually it'd be neat to have a set devoted to 1920s–30s Japanese college comedies, in general -- a robust genre.

- What A Disgrace

- Joined: Sun Nov 07, 2004 10:34 pm

- Contact:

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

I had a dream last night in which I popped in Second Run's upcoming DVD of Jiri Menzel's Larks on a String, only it turned out to be a late period Ozu film, in which Chishu Ryu was a former Olympic Gold Medal winning swimmer, trying to patch things together with his son, who was also going to be an Olympic swimmer.

It was the most enjoyable dream I've had in years.

It was the most enjoyable dream I've had in years.

- Michael Kerpan

- Spelling Bee Champeen

- Joined: Wed Nov 03, 2004 1:20 pm

- Location: New England

- Contact:

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

Interesting dream ;~}

Ryu was a star cross-country runner in Shimizu's Star Athlete... But can't think of any REAL films which feature him as a swimmer. (Takeshi Sakamoto, however, has to do a fair bit of swimming at the end of Passing Fancy).

Ryu was a star cross-country runner in Shimizu's Star Athlete... But can't think of any REAL films which feature him as a swimmer. (Takeshi Sakamoto, however, has to do a fair bit of swimming at the end of Passing Fancy).

- ambrose

- Joined: Wed Sep 08, 2010 2:16 pm

- Location: Durham United-kingdom

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

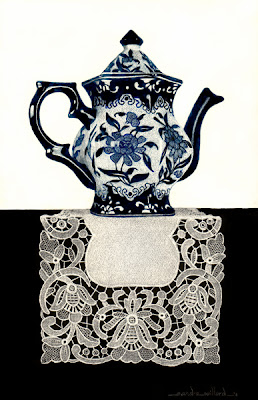

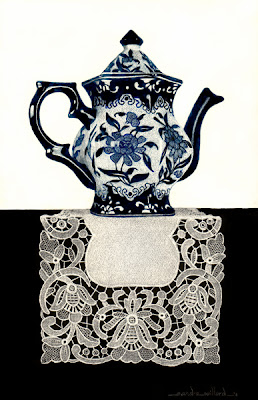

Tea for Ozu

Sandra Willard wrote:The title for this still life comes from my love of director Yasujirō Ozu's movies. One of his signature elements was to place a teapot somewhere in the frame of a scene and he always filmed from a "tatami" angle. You can read more about this talented director here. I realize that my teapot is far more ornate than the ones he used however it is intentional and was selected as a deliberate contrast to the simplicity of the composition.

- bottled spider

- Joined: Thu Nov 26, 2009 2:59 am

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

Well, now I know what a scratchboard is. I took that for a photograph at first.

- ambrose

- Joined: Wed Sep 08, 2010 2:16 pm

- Location: Durham United-kingdom

- knives

- Joined: Sat Sep 06, 2008 6:49 pm

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

I'm a bit shocked into silence so I'll make this quick. I think A Hen in the Wind is top three Ozu for me now (also the BFI disc is gorgeous). Even beyond the more shocking elements if the film I'm stunned at the depression of all of this. It's the only Ozu film to not have me laugh and it earns that completely.

- Michael Kerpan

- Spelling Bee Champeen

- Joined: Wed Nov 03, 2004 1:20 pm

- Location: New England

- Contact:

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

I would say that -- for me -- Toktyo Twilight is grimmer (and even more laugh free) than Hen in the Wind.

To me, the most shocking scene in HitW is the one in which our heroine's "customer" eats after his "visit" with her. The grossness of his eating habits is clearly intended to represent his grossness in carrying out other activities. One really pities our heroine...

To me, the most shocking scene in HitW is the one in which our heroine's "customer" eats after his "visit" with her. The grossness of his eating habits is clearly intended to represent his grossness in carrying out other activities. One really pities our heroine...

- knives

- Joined: Sat Sep 06, 2008 6:49 pm

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

Oddly enough I find Twilight less grim. It's a tough contest certainly, but Twilight is running to the grime while Hen seems to wallow in it. Either way they're tough watches and the way these fallen women movies should be done (though to call Tokiko fallen would seem to miss the point).

I agree that's a very frightening scene and the subtle shock sets will probably haunt me tonight more than the explicit stuff even if those pieces were needed. I do want to pity her, like you said, but there's something in the film (maybe it's her interactions with her son) that make such a reaction feel wrong. She deserves something, but pity sounds too degrading for her.

I agree that's a very frightening scene and the subtle shock sets will probably haunt me tonight more than the explicit stuff even if those pieces were needed. I do want to pity her, like you said, but there's something in the film (maybe it's her interactions with her son) that make such a reaction feel wrong. She deserves something, but pity sounds too degrading for her.

- Michael Kerpan

- Spelling Bee Champeen

- Joined: Wed Nov 03, 2004 1:20 pm

- Location: New England

- Contact:

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

Ozu is -- I think -- telling us that his heroine deserves not pity but respect.

HitW seems to have a very unique look and feel -- very different from Ozu's other works.

HitW seems to have a very unique look and feel -- very different from Ozu's other works.

- knives

- Joined: Sat Sep 06, 2008 6:49 pm

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

You're right, respect is definitely the word I was looking for. For all of the differences in the film (in many ways it's a New Wave film) I think it's still strongly and excellently Ozu. All the similarities I think make the differences more powerful and unique. If anything this is a perfect highlight to why those things of story and style work so well.

- puxzkkx

- Joined: Fri Jul 17, 2009 12:33 am

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

This is something I wrote for school comparing Ozu and Oshima in their approaches to postwar Japanese value changes. I'm a bit embarrassed to post a uni essay here, but I'm really curious as to whether anyone else reads this kind of social allegory into Ozu. I've seen most of his 50s and 60s work and I can detect this kind of sociopolitical symbolism in every film - overtly (like in Ohayo or in An Autumn Afternoon) or more implicitly (Tokyo Story, Floating Weeds et al). He has that rep as the "quintessential Japanese director" but tbh I find him quite cynical about Japan, although not necessarily in an angry or mean-spirited way a l'Oshima. However I say this as someone who hasn't seen any of his wartime or pre-war films (Late Spring is my earliest) so maybe I'm projecting. Anyway:

Superficially, the works of the Japanese directors Yasujirō Ozu and Nagisa Ōshima present dramatically divergent depictions of postwar Japanese life. Their respective catalogues could hardly be more formally dissimilar, and the narrative concerns of their 1950s and 1960s work stand in stark contrast. It seems difficult at first to reconcile the reticent family dramas of Ozu’s 1950s with the fuming polemics of Ōshima’s 1960s. However, the striking differences in style and content between the two belie a common thematic concern with, and attitude towards, postwar changes in Japanese social values.

The structural-formal disjunctions of the two directors’ approach to filmmaking are immediately noticeable, and they are present at the most foundational, grammatical level. Yasujirō Ozu is known for his framing, shooting from a low camera height often erroneously described as emulating the eyeline of a person sitting on a tatami mat (in actuality the placement is far lower). His mise-en-scène is obsessively controlled, with lines and grids leitmotifs that echo the criss-crossing relationships of the extended families he depicts in his sober, quiet domestic dramas. Although there are rare instances of dolly motion in his œuvre (in his later work best exemplified by The Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice (1952)), Ozu predominantly worked with long, static shots that exploited depth of frame through the careful position of furniture, hallways and doors. Punctuating his films are his trademark ‘pillow shots’, cutaways which move away from nearby action to focus on narratively unrelated objects or settings. His editing is generally simple, hard cuts occasionally spiced with dissolves or fades. Ōshima also used long takes but in them developed complex sequence shots with highly sophisticated camerawork and a use of space reminiscent of avant-garde theatre directors such as Brecht. His editing is flamboyant, playing with kaleidoscopic crossfades (Pleasures of the Flesh (1965)), hidden dissolves (Night and Fog in Japan (1960) and The Christian Revolt (1962)) and occasionally sojourning into still-photo montages and documentary sequences (Death by Hanging (1968)). The mise-en-scène of his pictures is often stark, his sets sparely dressed unless necessitated by story to be cluttered - as in the case of the squalid gangsters’ hovels in The Sun’s Burial (1960). Circular shape and motion permeate his films, often manifesting in perverse appropriations of the Japanese flag, eternal symbol of his dissatisfaction with the state of the state.

These stylistic differences are not indicative of alien thematic interests, however. Ozu and Ōshima are not simply dissimilar; rather they have an antonymous relationship. There is a polarity to their use of cinematic resources, but they are two sides of the same coin in that they basically answer each other in their treatment of specific narrative codes. This analogue goes deeper than mere style - the directors’ historical placement and approaches to production were nearly opposite, too. Yasujirō Ozu made his last feature film in 1962, Nagisa Ōshima made his first in 1959. Ozu worked diligently for the production company Shōchiku for over three decades, making all but three of his features for them, content to cooperate with the studio system. Known for producing shomin-geki, realist dramas of everyday life, it fostered Ōshima as well in his early days as a filmmaker - his debut feature, the relatively classical A Street of Love and Hope (1959), fit quite comfortably in the Shōchiku wheelhouse. Ōshima, however, found the studio environment restrictive and inimical to the confrontational political rhetoric he wanted to explore. His fourth film, the formally experimental cross-examination of protest politics Night and Fog in Japan (1960), was pulled by Shōchiku after four days in theatres. After this Ōshima went freelance and, aside from a last gasp for Toei with the jidai-geki (period piece) The Christian Revolt (1962), it would be years before he directed for another studio.

If Ozu was always a social director and Ōshima a political one, this was evident in the structural specifics of their mid-century work. Ozu’s exploration of shifting values focused on their micro-level, personal and interpersonal effects, whereas Ōshima explored the fallout across wider social strata. Both directors, however, presented social units as microcosms of Japan - in Ozu’s case it was the family, generational divides echoing the tensions of ‘old’ (pre-surrender) and ‘new Japan’. Ōshima, most prominently in films from his early 60s period such as The Sun’s Burial (1960) and Cruel Story of Youth (1960), used the gang or political group, hierarchies and feudal relationships providing similar symbolic definition. In fact, both directors showed a similar fascination with a gallery-style method of character development, where different members of a group represented different approaches or solutions to a social or political issue. This can be seen in early Ōshima pictures from Night and Fog in Japan, where the attendees of a reunion of former student radicals each embody a different facet of the Japanese New Left’s 1950s & 60s political activity, to Death by Hanging, where a committee of officials witnessing an (unrealised) execution index the perspectives of various political and cultural institutions on both capital punishment and the treatment of Korean immigrants in Japan.

Ozu’s use of this method is particularly potent in his penultimate film, 1961’s The End of Summer. The film can function as a compendium of the themes and narrative devices he revisited throughout his career: the process of omiai (arranged marriages) and generational attitudes towards it, death and aging, and the relationships between members of extended families. Here, as in many of his works, he used those themes to explore a nation in social flux, one where the major trauma of the war had created a potentially impassable divide between old and young generations. In the film Manbei Kohayagawa, the widowered owner of an ailing Kyoto sake brewery and father of three - possibly four - daughters, tries to balance the rehabilitation of his business with a (re)blooming relationship with an old flame who lives in Osaka. He lives with his eldest daughter, Fumiko, her husband and their children. His second daughter, Akiko, and his youngest Noriko live together in Osaka, the former a curator at an art gallery and the latter a secretary. Akiko is the widow of an intellectual and she has a young son. Manbei organises omiai interviews for both Akiko and Noriko, and their ambivalent responses to these proposals create conflict within the family. His ex-lover Sasaki has a daughter, Yuriko, who she casually refers to as Manbei’s child although exchanges late in the film indicate this may not be the case. Yuriko is Westernised and materialistic, begging Manbei to buy her expensive furs and heading out every night with a different American beau. The key to The End of Summer’s social observation lies in the way it develops the four daughter characters as avatars of the tradition-modernity dialectic, presenting each as symbolic of a different sociocultural path Japan could take.

Fumiko, the eldest and most conservative of the girls, takes care of her father as well as her husband and sons. She is irked by his “libertine” behaviour and takes offense to his not-so-secret daily trips to Osaka. Ozu offers her as a vision of a ‘potential Japan’ that embraces its tradition and upholds ancient values, perhaps naïvely in the face of globalisation and widespread social change. Akiko, the intellectual’s widow, blends a sensitivity to the ‘family values’ of the past (she was married and is raising a son) with an openness to modern thought and value systems (she works at an art gallery that shows international pieces). Noriko, the youngest, shares more than a name with the Noriko of Ozu’s most famous films - Late Spring (1949), Early Summer (1951) and Tokyo Story (1953). Like that Noriko (who was played by Setsuko Hara, the actress playing the Akiko role in this film), she is free-spirited compared to her elders, more attuned to the viability of Western relationship models and more skeptical regarding omiai and its efficacy in providing long-term stability and satisfaction. In The End of Summer she rejects the marriage interview despite claiming to have been charmed by the suitor, and at the end of the film leaves for faraway Sapporo, following the former boss with whom she had fallen in love. The Japan embodied by Noriko forges its own path in the world, leaving old ways of thinking behind and staying detached from custom (Noriko is the only ‘legitimate’ daughter who is seen wearing Western clothing) while retaining a respect for it and its history. The character of Yuriko is a surprisingly cynical creation, her possible illegitimacy a clever shorthand for the intergenerational relationships of the social movement she represents. She is decked out like Sandra Dee, stepping out with a different American every night and, upon Manbei’s eventual death, not mourning him but rather mourning the prospect of a free mink stole. She is the epitome of the Westernised Japan, rejecting tradition completely and moving with a smile towards the culture responsible for both her destruction and her genesis. The picture ends on an ominous note, focusing on Manbei’s grave, flanked by crows. Here Japan is left without guidance from the ‘old guard’: the girls, and the country, have been left at a junction and it is up to them to create their own future. It is a quiet but powerful ending, like so many of Ozu’s, the smoke from the crematorium chimney recalling Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s mushroom clouds and throwing the necessity of this cultural ‘future-claiming’ into deeper relief.

If Ozu saw conservative characters like Fumiko or Manbei - defensive of omiai despite his ‘bad behaviour’ in Osaka - as products of their cultural environment and therefore free from judgment, Ōshima saw his characters as products of their environment, but to be held accountable anyway. His films are defined by their anger, his political rage powerful enough to cleave the structure of the film itself, as in the black comedies Death by Hanging and Three Resurrected Drunkards (1968), where the need to take the nation to task crystallises in grand subversions of narrative temporality (a sublimation into dream logic in the former, a shot-by-shot repetition in the latter). While Ozu was elegiac in his treatment of fading tradition, evoking that quintessentially Japanese feeling of mono no aware, or a sensitivity to transience, Ōshima was much the opposite. His rejection of tradition approaches full-blown futurism; he looks at custom as a toxic force that is nothing more than a relic of Japan’s imperialist past. This view of tradition as a destructive social malaise shapes the central conceit of his 1971 film The Ceremony. Here a sprawling upper-crust family, riddled with sins secret and not-so-secret, is placed under a microscope. Their history is told in a vignettish flashback structure that focuses on their meetings during important ceremonies such as weddings and funerals. The wanton behaviour of the characters is weighed against the reverent attention they give ritual, and the compulsion of the Japanese family to mediate its relationships with meaningless ceremony is given as both cause and evidence of its decline and increasing powerlessness. In the film’s most famous sequence, a groom is stood up at the altar. However, his elders force him to go through with the ceremony anyway, ‘marrying’ nothing but thin air.

Ōshima and Ozu shared a focus on dysfunctional adult-youth relationships. A scan of Ozu’s films reveals a recurrent theme of conditional relationships across generational divides. In Early Summer a grandfather gives his grandson a biscuit every time he says “I love you”. When he finally withholds a treat the child says “I hate you”. In one of his few late comedies, Ohayō (1959), two boys take a vow of silence, refusing to break it until their parents buy them a television. In both of these instances these relationships are presented in a humourous context, but Ozu’s focus on these kinds of conditional bonds implies issue taken with traditional Japanese relationship models, regardless of the respect he has for the culture’s custom and ritual. The fact that most of these depictions involve children implies a prediction of even greater disconnection from social history in the upcoming generation. Ōshima’s depiction of the generational divide was far grimmer, painting Japanese youth as locked in a vicious, often violent, cycle of exploitation and rebellion with their elders. In the film that first earned him critical kudos in Japan, his sophomore effort Cruel Story of Youth, the waifish lead character prostitutes herself out to lonely salarymen before letting her boyfriend/abuser/pimp - in Ōshima’s universe such criteria of identity are never mutually exclusive - beat and rob them. Perhaps most revealing is the depiction of the slum in The Sun’s Burial, where youth gangs rule while the elderly are trapped in their own corrosive patterns of prostitution - of flesh, of skill, of identity - and extortion. These patterns are tellingly defended by one character, an aged war veteran who demands to be addressed by his military title and rejects, out of a sense of entitled imperialist machismo, any culpability for his rapes and thieveries.

Those two films were marketable by virtue of their superficial affiliation with the “sun tribe” genre - a popular wave of films focusing on rebellious youth. At the same time, however, they form a deconstruction and indictment of that genre. Ōshima makes it clear that to romanticise the plight of such wayward youth is to push them further away from the promise of effective political agency. He illustrates a generation disenfranchised by poverty, misplaced government interest and war, trying desperately to reconcile their aimless existence with the ghosts of an imperialist history. The boys do this through the pantomime of ancient - and violent - representations of Japanese masculinity: the samurai, the yakuza and the soldier. They form gangs out of a shared sense of alienation, killing and beating without thought because even their own lives mean nothing to them. For the girls this can manifest as a grotesque geishaesque subservience, epitomised by the Makoto character in Cruel Story of Youth who, in a scene that summarises her entire narrative arc, is pushed onto the dance floor by her lover-abuser and is shoved between him and several other men, spinning and wagging her hips confusedly all the while. This confusion of pleasure and pain and of role and personality is met from the opposite direction by the Hanako character in The Sun’s Burial, a misanthrope who disdains her sex completely, using it to get what she wants but seemingly less bothered by the fact of her father’s sexual harassment than by the fact that he’s doing it while she’s trying to sleep. The films have a lot in common in the way they approach the ‘youth film’ model, but it is both powerful evidence of the generation’s dual ‘death drive’ for both destruction and self-destruction and a testament to the feminism inherent in Ōshima’s work that he can at the same time let Makoto be the weakest character in Cruel Story and Hanako the strongest in Burial.

Ozu’s similar concern for women and youth was just as pointed thematically if not dramatically. While his films are often said in the West to be “typically Japanese” in style and point-of-view , it is undeniable that he balances a respect for the culture and its fallibility with a protesting voice directed towards the rigid social structures handed down from the old to the young. His disdain for omiai is clear, and there is a bitter edge to the recurring images of history in his films. As in Floating Weeds (1959) the motif of traditional theatre becomes shorthand for the futility of the ways in which contemporary Japan tries to connect with its old self. Traditional theatre makes appearances in many late Ozu films - Late Spring and The Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice among them - but here its symbolic potential was most wholly realised. A troupe of actors, dressed in historical garb, visit a seaside village of particular importance to their master actor. Here he left a lover and a son, the latter now a young man but still in the dark as to the truth about his relationship with the man he only knows as his uncle. The actor kept his paternity a secret out of paranoia regarding arbitrary class distinctions of which the young man knows little and about which he cares even less. The village is rural, but many of its inhabitants wear Western clothes, contrasted with the complex ceremonial getups of the visiting performers. Their material is antique; their repertoire has remained unchanged for years. There is a sense that they are out of their depth here, that their representations (and re-presentations) of history are unwelcome or at least not commanding of the same respect as they were ten years before, directly after the war - the last time they had visited the town. A line is drawn between the compulsive engagement in ritual, lampooned so viciously by Ōshima in The Ceremony, and acting - offered as the only way in which Japan can now replicate its past. In this way the desperate maintenance of tradition is not genuine, but as put on and routine as the performances of the itinerant troupe.

Viewing Nagisa Ōshima and Yasujirō Ozu side-by-side is disorienting. The differences are striking but the similarities almost more so. In their first and final decades, respectively, they had ideas to spare - Ozu made 12 feature films in the 50s, and in the 60s Ōshima made a whopping 14. The fallout of the war and the surrender casts a shadow across most, if not all, of their films from this time, and its influence unifies thematic concerns for these directors. Ōshima, who was a critic before moving into directing, hated the “premodern” humanist cinema of 1940s and 1950s Japan and would have seen Ozu as emblematic of the nostalgic cultural fixations he despised. As for Ozu, one can’t imagine the famously reserved director easily warming to Ōshima’s particular brand of furious formal and narrative radicalism. However, despite the yin-yang of their formal approaches, an examination of their responses to the changes in Japanese value systems after WWII shows that there is plenty of each in the other.

- Michael Kerpan

- Spelling Bee Champeen

- Joined: Wed Nov 03, 2004 1:20 pm

- Location: New England

- Contact:

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

Interesting article. I think one needs to factor into the Ozu analysis the fact that on the occasions he felt moved to tackle social and/or political issues more directly (Record of a Tenement Gentleman, Hen in the Wind and Tokyo Twilight), his films met with critical and popular rejection. One might also note that not only Tokyo Twilight abut also Early Spring exhibit a sense of under-the-surface anger that anticipated the more overt social anger of the soon-to-come "sun tribe films". I get a sense that the Shochiku rebels (none of whom were apparently big film fans in their youth) were not aware of Ozu's less "tranquil" films -- but only those films that he made after taking to heart the rejection of those films.

- puxzkkx

- Joined: Fri Jul 17, 2009 12:33 am

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

^ I can buy that. For example I know that Oshima was no fan, but I feel like an interpretation of later (esp. colour) Ozu as criticisms of Japan's efficiency in dealing with postwar cultural problems is quite accessible and perhaps he'd have changed his tune were he to look at them as something more than 'relics' of a classical form of storytelling (and Ozu was not particularly classical compared to, say, his contemporary Mizoguchi)!

I saw An Autumn Afternoon after I wrote that essay, and I feel that its attack on a Japan that 'wants it both ways' - to produce a culture that accepts the choices of the young (symbolised by the daughter's reluctance to get married) or remain comfortably entrenched in the quickly outdated imperial mindset (Ryu's character's peer pressure by his corporate buddies and his memories of the military march) but cannot find the will, or strength, to create that happy balance. Ozu presents the idea that respecting the wishes of both father and daughter, the (tiny) family unit here representing the core concerns of the rapidly changing Japan, would create harmony for all concerned. The fact that this potential is broken at the end gives the finale a sense of both personal and cultural loss and failure. I think it is cynical but beautiful - it almost feels like 'giving up', by the character, on the character, on Japan and - given that this was his last film and he almost certainly knew it would be while filming it - on life: this makes it the most devastating Ozu film for me, I was in shock at the end.

The 50s films you listed are some of the few that I haven't seen - for the record I based my analysis on a viewing catalogue of Late Spring, Early Summer, Tokyo Story, The Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice, Ohayo, Floating Weeds and The End of Summer, and I watched An Autumn Afternoon later.

I saw An Autumn Afternoon after I wrote that essay, and I feel that its attack on a Japan that 'wants it both ways' - to produce a culture that accepts the choices of the young (symbolised by the daughter's reluctance to get married) or remain comfortably entrenched in the quickly outdated imperial mindset (Ryu's character's peer pressure by his corporate buddies and his memories of the military march) but cannot find the will, or strength, to create that happy balance. Ozu presents the idea that respecting the wishes of both father and daughter, the (tiny) family unit here representing the core concerns of the rapidly changing Japan, would create harmony for all concerned. The fact that this potential is broken at the end gives the finale a sense of both personal and cultural loss and failure. I think it is cynical but beautiful - it almost feels like 'giving up', by the character, on the character, on Japan and - given that this was his last film and he almost certainly knew it would be while filming it - on life: this makes it the most devastating Ozu film for me, I was in shock at the end.

The 50s films you listed are some of the few that I haven't seen - for the record I based my analysis on a viewing catalogue of Late Spring, Early Summer, Tokyo Story, The Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice, Ohayo, Floating Weeds and The End of Summer, and I watched An Autumn Afternoon later.

- Michael Kerpan

- Spelling Bee Champeen

- Joined: Wed Nov 03, 2004 1:20 pm

- Location: New England

- Contact:

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

After the very upsetting rejection of Tokyo Twilight (which was very important to him), Ozu re-tooled and returned to the same basic theme that was rejected (namelyFather is NOT always -- or even often -- right) but handled with a sort of disarming, breezy humor.

I too feel that these late films are typically about the reconciliation (or at least non-hostile coexistence) of old and new ways -- both of which are seen by Ozu as valuable AND problematic.

Ozu had no idea that Autumn Afternoon would be his last film. He had already planned (and written, I believe) his next film when he began to experience symptoms of his (fast-moving) cancer.

I too feel that these late films are typically about the reconciliation (or at least non-hostile coexistence) of old and new ways -- both of which are seen by Ozu as valuable AND problematic.

Ozu had no idea that Autumn Afternoon would be his last film. He had already planned (and written, I believe) his next film when he began to experience symptoms of his (fast-moving) cancer.

- puxzkkx

- Joined: Fri Jul 17, 2009 12:33 am

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

Yes, of course, Ozu was not a futurist in the way Oshima was. He took issue with many aspects of 'new Japanese values'/Western cultural exchange - Reiko Dan's character in The End of Summer is proof of that!

It may be to do with his mother, then, rather than himself - I feel like An Autumn Afternoon is charged with an atmosphere of death.

It may be to do with his mother, then, rather than himself - I feel like An Autumn Afternoon is charged with an atmosphere of death.

- Michael Kerpan

- Spelling Bee Champeen

- Joined: Wed Nov 03, 2004 1:20 pm

- Location: New England

- Contact:

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

Death hovers around many of Ozu's films from Early Spring (death of a young-ish colleague of the male protagonist) onwards....

- puxzkkx

- Joined: Fri Jul 17, 2009 12:33 am

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

I don't mean in terms of content - in terms of overall mood An Autumn Afternoon is darker than something like, say, The End of Summer which deals primarily with death. It is as if the question posed in the final shot of The End of Summer - "where to now?" - is answered in An Autumn Afternoon with "nowhere".

- Michael Kerpan

- Spelling Bee Champeen

- Joined: Wed Nov 03, 2004 1:20 pm

- Location: New England

- Contact:

Re: Yasujiro Ozu

I guess I see these films differently. I find Autumn Afternoon remarkably light-hearted overall, despite occasional darker moments. Our family laughed more during this than during any other Ozu film (except maybe Lady and the Beard).