Agreed. Irma is Wilder's most disappointing film in my opinion, though, strangely enough, it was actually his highest grossing picture. Aside from The Apartment, I think One, Two, Three remains the most enjoyable thing Wilder did in the decade. Its antic zaniness rivals the best of the screwball comedies from the 30s and 40s.zedz wrote:Latest viewing was Irma la Douce, which was distressingly lame: painfully overextended and unfunny. No doubt very 'risque' in its day, it hasn't aged at all well.

1960s Discussion and Suggestion (Lists Project Vol. 2)

- souvenir

- Joined: Wed Nov 03, 2004 12:20 pm

- Cold Bishop

- Joined: Tue May 30, 2006 9:45 pm

- Location: Portland, OR

I can't help but ask zedz, with Japanesenewwave.com gone, how do you keep viewing these films.

Honestly, the only deterrent keeping me from submitting a list is the large amount of movies that I feel from reading and word-of-mouth are essential to see before making any sort of opinion of the decade. With the sixties, these are mostly made up of Imamuras, Oshimas, Shinoda, Masumuras, Hanis, etc.

I really hate to turn this into something that should be better off in the "bootleg" thread, but while I'm trying to put together such a list, I can't help but feel very disheartened by the large amount of "must-see" movies that I know are out there, but I cant seem to track down.

Honestly, the only deterrent keeping me from submitting a list is the large amount of movies that I feel from reading and word-of-mouth are essential to see before making any sort of opinion of the decade. With the sixties, these are mostly made up of Imamuras, Oshimas, Shinoda, Masumuras, Hanis, etc.

I really hate to turn this into something that should be better off in the "bootleg" thread, but while I'm trying to put together such a list, I can't help but feel very disheartened by the large amount of "must-see" movies that I know are out there, but I cant seem to track down.

- Scharphedin2

- Joined: Fri May 19, 2006 7:37 am

- Location: Denmark/Sweden

Yes, I viewed the Facets release, and although I am not about to blunder into recommending anything with Facets' name on it, I would say that this release is closer to the "best" of their efforts, than it is to their "worst."zedz wrote:Thanks for the White Dove tip. Was that a Facets release?

I am happy to see that I will likely not be the only one to cast a vote for Billy Wilder in the ‘60s. To me, he belongs to that first group of directors that I became aware of as directors in my early teens, and the film that introduced me was a TV broadcast of The Apartment. Since then, I have seen almost all of Wilder's films, but The Apartment is still the one (aside from everything else it has going for it) that I can always come back to and experience all the basic pleasures of simply watching a fun and entertaining film. One, Two, Three is the obvious competitor from the decade, but I also think that The Fortune Cookie has its moments; in fact, it is completely outrageous – to me the seminal pairing of Lemmon and Matthau.

Some quick comments on a few ‘60s films that I have viewed recently:

Elia Kazan's Wild River. I think this is first a really gorgeous cinemascope film – in terms of the use of color and composition, it is very obviously the sibling of East of Eden. The story concerns an official of the American government, who is sent to the Tennessee Valley in the 1930s to lead the evacuation of an area that will be flooded as an effect of the erection of a dam. In the telling of his story, Kazan manages to touch on several of the important issues of his own day in relation to race, gender, and constitutional rights, without losing sight of the human story(-ies). The element that most viewers can usually agree on with Kazan's films is the quality of the performances, and there are some exceptional ones in this film as well – Montgomery Clift and Jo Van Fleet, of course, but Lee Remick touched me above all.

Samuel Fuller's Underworld, USA. The title says it all; Fuller tells an archetypal tale of revenge in a manner that feels as if you are in the ring with a prizefighter. The pace is brisk, and the cinematic language is blunt and kinetic. A man is beaten to death by four hoodlums in a back alley, and we see it all in silhouette on a wall. A gorgeous blonde teen hooker has been beaten by her pimp, and Fuller allows the audience to take in the bruises in long close-ups of her face. The drowning of a fat man is accomplished by pushing him under and standing on his shoulders. The film would fit in nicely with the gangster dramas and noirs of the ‘30s and ‘40s, the main difference being that Fuller's way of talking is much more direct.

Ingmar Bergman's The Virgin Spring. Despite my Scandinavian origins, I have not been that attracted to Bergman in the past, but I was deeply impressed with this film. I liked the idea that Berman built his film on a folk ballad -- a short tale of a crime and its revenge set in medieval times. Several weeks later, the film is still vividly with me, particularly the moment close to the end, where Von Sydow wrenches a birch tree from the ground with his bare hands – the violence and almost arbitrary nature of this act, when we well know what the scene anticipates. The film is structured around two other scenes of harrowing and highly graphic violence, but to me it was this short moment that bore the very strongest emotional impact.

Ermanno Olmi's Il Posto. I am not sure what the correct term for Olmi's particular brand of “realistâ€

- tryavna

- Joined: Wed Mar 30, 2005 4:38 pm

- Location: North Carolina

I suppose the short -- and simplistic -- answer is that it was by necessity (i.e., in response to the difficulties on immediate post-war conditions). Of course, I'd be kind of interested in hearing whether or not you think the realist/documentarist tradition continued much beyond the classic boundaries of the Neorealist period. Watching later Visconti, Fellini, etc., as well as Leone, Bava, etc., I've always gotten the impression that the Italians couldn't wait to get back into the studio so that they could re-embrace stylization.Scharphedin2 wrote:One question I quickly throw out there in closing, as I need to finish my coffee and get going -- why, with this most romantic of peoples (the Italians), has the tradition of realism and documentarism been so particularly strong in the country's film history?

This is a very genuine question from me. I just attended an interesting presentation on Neorealism yesterday, so I've been thinking about Italian directors quite a bit during the past 24 hours.

- Awesome Welles

- Joined: Fri Apr 27, 2007 6:02 am

- Location: London

It seems like such an easy answer that maybe it isn't the answer at all, but perhaps this is due to the fact that all the directors grew up during the war and were assistant directors or directors themselves during the neo-realist period.Scharphedin2 wrote:One question I quickly throw out there in closing, as I need to finish my coffee and get going -- why, with this most romantic of peoples (the Italians), has the tradition of realism and documentarism been so particularly strong in the country's film history? DeSica, Rossellini, Antonioni, Visconti, Olmi, Rosi, Scola, Amelio, to just list a few of the bigger names... all of them began their careers with films in the realist/documentary vein.

I always feel that a country's traditions, whether these be literary or originating from the stage inform their cinematic practices. Of course one also has to take into account what political changes have informed their artistic practices. Both World Wars provided (in Europe) impetus for not only propagandistic practices but also, in the case of Italy, a backlash on the promotion by the Italian goverment that Italy was in a strong position. The filmmakers sought to reveal the truth and expose (to use a Cuban phrase) a country of underdevelopment, where people were suffering. Perhaps this need to unveil a truth inscribed artistic practices in those young Italian filmmakers and this was thus carried forward, whereby many new and young filmmakers forgot, for a long time, what it was like to make films that were any different.

Italy of course has suffered at the hands of much corruption and filmmakers like Francesco Rosi have sought to tackle these issues. Rosi is, as those who have seen his films know, a great aesthete. His films are wonderfully stylised and in my opinion you really do get the best of both worlds. He provides a great bridge between neo-realism and the latter stylisations of Italian cinema. It may just be that, like the old phrase "if it isn't broken, don't fix it". The documentary/realist aesthetic may just be the best way to get a point across. Godard's agit-prop didn't work because no one saw it, whereas everyone saw neo-realism in the 40s, I can't comment on the 1960s as I have no idea of the cinema admissions.

- Scharphedin2

- Joined: Fri May 19, 2006 7:37 am

- Location: Denmark/Sweden

I think that necessity is only part of the answer. Clearly DeSica, Rosselini, Visconti and other directors, who began their film careers right around the time of World War II and in the years immediately following made the films they did with the means at their dispossal, and also to a degree in response to the socio-economical conditions in Italy following the war. Even the early realist films and documentaries by Fellini and Antoinioni can be explained this way.

However, the thought struck me, because even with directors arriving on the scene later, I think there is the same pattern to an extent. To begin with Olmi and Rosi, these directors made their first films in 1953 and 1952 respectively; Olmi made more than a score of documentaries, before breaking into narrative films in the sixties, and Rosi's first handful of feature films were very rooted in the documentary tradition. With these two, one could say that they remained committed to social issues throughout their careers, and that they have retained elements of the realist-documentarist school in their work. Pietro Germi was of the same generation (although he began as a screenwriter already during the war), and as far as I know his earlier work is rooted in realism, but then later he moved on to make the better known comedic films.

Then we have directors like Bertolucci and Pasolini who do not make their debuts until the '60s, but then with films that are very influenced by neo-realism and documentary film styles. And, even bringing the argument up to date, I think the argument can be made that the early work of directors such as Amelio (Ladro di bambini and L'America) and Tornatorre (Nuovo Paradiso and Stanno Tutto Bene) also is quite rooted in the realist tradition.

I have not seen nearly enough Italian cinema to justify making any real statement on this. It just struck me as interesting that so many of the filmmakers I am familiar with out of Italy share this realist or documentarist strain in their early work. Needless to say Leone and Bava do not fit into this pattern, as Tryavna points out above.

I would be curious to read the thoughts of posters with a greater knowledge of Italian film than me.

However, the thought struck me, because even with directors arriving on the scene later, I think there is the same pattern to an extent. To begin with Olmi and Rosi, these directors made their first films in 1953 and 1952 respectively; Olmi made more than a score of documentaries, before breaking into narrative films in the sixties, and Rosi's first handful of feature films were very rooted in the documentary tradition. With these two, one could say that they remained committed to social issues throughout their careers, and that they have retained elements of the realist-documentarist school in their work. Pietro Germi was of the same generation (although he began as a screenwriter already during the war), and as far as I know his earlier work is rooted in realism, but then later he moved on to make the better known comedic films.

Then we have directors like Bertolucci and Pasolini who do not make their debuts until the '60s, but then with films that are very influenced by neo-realism and documentary film styles. And, even bringing the argument up to date, I think the argument can be made that the early work of directors such as Amelio (Ladro di bambini and L'America) and Tornatorre (Nuovo Paradiso and Stanno Tutto Bene) also is quite rooted in the realist tradition.

I have not seen nearly enough Italian cinema to justify making any real statement on this. It just struck me as interesting that so many of the filmmakers I am familiar with out of Italy share this realist or documentarist strain in their early work. Needless to say Leone and Bava do not fit into this pattern, as Tryavna points out above.

I would be curious to read the thoughts of posters with a greater knowledge of Italian film than me.

- zedz

- Joined: Sun Nov 07, 2004 7:24 pm

JNWC was the key. They pretty much covered Imamura during their brief existence. My Oshima viewing is thanks to the JNWC titles, the three Raro titles, and a couple of kind donations from a friend (a copy of Kino's OOP Violence at Noon VHS and an alarmingly shonky, but gratefully received, Three Resurrected Drunkards from who knows where). With the even more elusive Yoshida I've had to make do with similarly clandestine, or unsubbed, sources. Joen, which will definitely be making my 60s list, looks like a digitalisation of a dub of a VHS of a long-forgotten TV screening, for instance. You take what you can get. Has any other film movement as major as this been so poorly served by English-subtitled DVD?Cold Bishop wrote:I can't help but ask zedz, with Japanesenewwave.com gone, how do you keep viewing these films.

Don't be deterred. The more you see the more gaps you'll perceive. When I saw She and He way back when, I was happy just to 'knock off' another New Wave director, but when I finally caught up with the blinding Inferno of First Love, I realised that I needed to track down all of his work. Even though Shinoda is probably the best-represented New Wave director, that just makes the missing titles that remain (e.g. Punishment Island) all the more frustrating.Honestly, the only deterrent keeping me from submitting a list is the large amount of movies that I feel from reading and word-of-mouth are essential to see before making any sort of opinion of the decade. With the sixties, these are mostly made up of Imamuras, Oshimas, Shinoda, Masumuras, Hanis, etc.

Which brings me back to my Oshima viewing. I've had to negotiate a considerable gap between Night and Fog in Japan from 1960 and 1966's Violence at Noon. That includes a couple of important features and the entirety of Oshima's extensive TV documentary work. Given how important documentary was to the form and content of his fiction films, I'm probably missing out on some serious light-shedding there.

Violence at Noon

I've already commented on this recently, but I have to rave some more. The editing style of this film is simply astonishing, and in drastic contrast to the long tracking shots of Night and Fog in Japan (I think Desser counts several thousand shots for this film, as opposed to Night and Fog's 43). And it's an editing style that owes as little to classic Hollywood editing as it does to modish Godard jumpcuts. Typically, Oshima will cover a given scene from a multitude of angles and distances, and create chains of edits that view the same material from different positions. In contrast to the earlier film, the camera is almost always static (the few exceptions are tilts, until we get to the penultimate scene in which the two female leads meet in a train carriage, which is covered by a series of mysterious and extreme back and forth pans), but the effect is one of constant, dynamic motion. The dense montage creates a sense of deconstructed camera movement: a series of shots of the same character from different angles being a deconstructed circular track, for example; a series of shots of the same character from different distances (ending up on an extreme extreme closeup of their eye, say) a deconstructed zoom. The use of the soundtrack is also arresting and original. When Shino has her first flashback during Eisuke's initial attack, it's totally silent, but when we return to her present, the sound only gradually bleeds back in. The content of this film is utterly compelling, but it's the style that keeps me rivetted to the screen every second.

Death by Hanging

This is where Oshima's thorny, dense mature style really emerges. As noted above, this film is closely related to Three Resurrected Drunkards (which I think barely preceded it), but TRD is sort of the streamlined, Chuck Jones version. Death by Hanging is an encyclopedia in comparison, though it's a prankster's encyclopedia. At one level, Oshima's 'messages' come through loud and clear: the death penalty is an abomination, Japan's treatment of Koreans ditto. But he piles so many different intellectual layers onto the absurdist premise (R, a convicted murderer, is hanged but fails to die) that the film sprawls into more dimensions than it - or you - can contain. In the course of the film, Oshima teases out the metaphysical, moral, legal, psychological, political and historical implications (and there's probably more angles I've overlooked) of R's failure to die, while all the time being strikingly staged and blackly funny. The officials need to get R to acknowledge his guilt, and his R-ness, before they can re-execute him, and they attempt to do this by ever more elaborate re-enactments of his crimes - Oshima's favoured cyclical structure is again evident. In this film, Oshima returns to his long, fluid takes, but they're less flashy than those of Night and Fog in Japan, and in general the style is much more staid than Violence at Noon, maybe because the content is anything but. I have immense respect for this film, but seeing it again, I loved it less than other 60s Oshimas, so while Violence at Noon will be racing up my list, this one's probably staying put. I should also put in a word for the film's trailer, one of the best I've seen. It's more like an incredibly informative "director's introduction" to the film, specifying the material's historical basis and clarifying the filmmakers' intentions. The series of mug-shots of the film's cast and crew is wonderful.

The Shooting

When, oh when is somebody going to give this film a decent release? The recent Madman edition has mediocre print quality and is in the incorrect 1.33 ratio, but I've never seen this on the big screen or in its correct ratio on the small one. Nevertheless, this is currently the only non-experimental American film that's still in my top 50 (I've had to do some pretty drastic jettisoning - even films that were in my top 20 last time around have been pushed off). Although the compositions are painfully, obviously wrong on this DVD (even to the extent of both major characters in a given shot being off-screen at some points), it still looks fantastic. The pitiless landscape is perfectly captured, and Hellman's placement of his characters in it is as expressive as Walsh or Mann. Plus there's the appallingly nihilistic, almost Beckettian storyline, with fantastic use of ellipses to keep us on edge, and three exceptionally great performances, with Nicholson tagging along behind the mighty Oates and Millie Perkins' ultimate femme fatale. What I also noticed this time around was the wonderful attention Hellman pays to the horses, prefiguring, perhaps, the fetishism of Two-Lane Blacktop? It's one of the few westerns where they're more than just props or local colour, but living, cohabiting creatures.

Ride in the Whirlwind

I've always felt this was the lesser of the two films, and still do, but it's nevertheless a fantastic achievement. Again, it's minimal and existential - Beckett is still a valid reference point - and again, there's more than a passing nod to film noir. No femme fatale this time, but the kind of oppression by fate you see in so many of those films is present and correct: the clang of Lang rings out through the wilderness. For me, there's less happening on the allegorical level, and the situation lacks the mystery (and a little of the horror) of The Shooting. Plus, there's no Oates (Cameron Mitchell is fine, but no substitute, and Harry Dean leaves early) and Millie Perkins is much more constrained. Nevertheless, a great film.

- Scharphedin2

- Joined: Fri May 19, 2006 7:37 am

- Location: Denmark/Sweden

zedz, I am not sure if you mean best-represented on R1, or best-represented anywhere. In any event, there is a release of Punishment Island out in Japan (if not oop) with English subtitles, released by Toho. The quality is quite good as I recall, and the price not exorbitant (apx. 4500 yen). I can post some stills later in the week, if you are interested.zedz wrote:Even though Shinoda is probably the best-represented New Wave director, that just makes the missing titles that remain (e.g. Punishment Island) all the more frustrating.

- zedz

- Joined: Sun Nov 07, 2004 7:24 pm

Great news - thanks a bunch. I tend to assume that any Japanese release of a film I want won't have English subtitles!Scharphedin2 wrote:zedz, I am not sure if you mean best-represented on R1, or best-represented anywhere. In any event, there is a release of Punishment Island out in Japan (if not oop) with English subtitles, released by Toho. The quality is quite good as I recall, and the price not exorbitant (apx. 4500 yen). I can post some stills later in the week, if you are interested.

- Cold Bishop

- Joined: Tue May 30, 2006 9:45 pm

- Location: Portland, OR

Are the full screen ratio I see on these correct?Lemmy Caution wrote:Charulata (1964) and Mahapurush (1965) are available on Dvd from Bollywood Films, with English and assorted European subtitles.zedz wrote:Abhijan

Is this really the only 1960s Ray readily available?

Unfortunately, I'm way behind in watching Indian films, and haven't gotten to them yet.

Maybe the 60's list-project-thang will act as a kick in the backside.

But I've got piles and piles to watch.

- Scharphedin2

- Joined: Fri May 19, 2006 7:37 am

- Location: Denmark/Sweden

Screen captures from the Japanese release of Punishment Island posted here. I apologise that the captures do not reflect the correct aspect ratio. There are (white) subtitles in English.

I also have to briefly gush about Mikio Naruse's Her Lonely Lane or A Wanderer's Notebook, which I had the privelege of seeing on a copy of a very old and worn video last night.

The film portrays the life of author Fumiko Hayashi, who provided Naruse with the literary material for many of his excellent films. Hideko Takamine stars, and it is one of the great film performances, and one of the great depictions of an artist's life that I have seen.

Hayashi is first seen peddling in the streets with her mother and father; they measure out their existence from meal to meal, and living more or less as vagrants. Abandoned by the love of her youth, Hayashi stays behind in the city, when her parents decide to try their luck in the country. Work is hard to come by, and Hayashi is not particularly well suited for any of the routine jobs that she manages to land. Gradually she drifts into a life as bar hostess, while nurturing a love of reading and writing at night by the flicker of candlelight.

She turns down the affection and proposal of marriage of a neighboring widower, and then gives herself to a would-be poet, who turns her head, but soon drops her in favor of a more glamorous and prosperous woman. Later she takes up with another writer, who suffers from consumption and is jealous of her ability to write. Slowly, she manages to have some short stories published, and we see her toward the end of the film on her way to literary fame.

Bridging the episodes of Hayashi's life that make up the film are Takamine's readings of selections from the author's poems and stories.

This life of misery, which Hayashi lived and immortalised in her writing, would appear to be one long monotonous journey colored grey. But, as one of the characters say, her writing is like a dust bin stirred with a stick, and its contents poured on the ground, only, even amongst the dust can be found real beauty. So too in Takamine's performance -- there are so many subtle nuances and changes in the look of her eyes, the way she casts her head and carries herself from scene to scene that, almost imperceptibly, we witness the development of this woman, as the life experiences slowly pile up on top of her. By the end of the film, the distant and indignant young woman has transformed into a worthy - if stoic and resigned - older lady. Hardly any make-up is used to achieve this, it is all in the performance.

I also have to briefly gush about Mikio Naruse's Her Lonely Lane or A Wanderer's Notebook, which I had the privelege of seeing on a copy of a very old and worn video last night.

The film portrays the life of author Fumiko Hayashi, who provided Naruse with the literary material for many of his excellent films. Hideko Takamine stars, and it is one of the great film performances, and one of the great depictions of an artist's life that I have seen.

Hayashi is first seen peddling in the streets with her mother and father; they measure out their existence from meal to meal, and living more or less as vagrants. Abandoned by the love of her youth, Hayashi stays behind in the city, when her parents decide to try their luck in the country. Work is hard to come by, and Hayashi is not particularly well suited for any of the routine jobs that she manages to land. Gradually she drifts into a life as bar hostess, while nurturing a love of reading and writing at night by the flicker of candlelight.

She turns down the affection and proposal of marriage of a neighboring widower, and then gives herself to a would-be poet, who turns her head, but soon drops her in favor of a more glamorous and prosperous woman. Later she takes up with another writer, who suffers from consumption and is jealous of her ability to write. Slowly, she manages to have some short stories published, and we see her toward the end of the film on her way to literary fame.

Bridging the episodes of Hayashi's life that make up the film are Takamine's readings of selections from the author's poems and stories.

This life of misery, which Hayashi lived and immortalised in her writing, would appear to be one long monotonous journey colored grey. But, as one of the characters say, her writing is like a dust bin stirred with a stick, and its contents poured on the ground, only, even amongst the dust can be found real beauty. So too in Takamine's performance -- there are so many subtle nuances and changes in the look of her eyes, the way she casts her head and carries herself from scene to scene that, almost imperceptibly, we witness the development of this woman, as the life experiences slowly pile up on top of her. By the end of the film, the distant and indignant young woman has transformed into a worthy - if stoic and resigned - older lady. Hardly any make-up is used to achieve this, it is all in the performance.

- zedz

- Joined: Sun Nov 07, 2004 7:24 pm

Diary of a Shinjuku Thief

It's hard for me to be objective about this film. As the first Japanese New Wave film I saw, it really tore the top of my head off, and it still has a similar effect on me. What I found / find so amazing about it is the sheer profligacy of its technique and the knottiness of its treatment of its subject (sexuality, crime, revolution, performance): "an unsolvable, solvable mystery". Oshima throws everything up on the screen: black and white (classical studio and grungy verite) and colour (with rogue Roeg reds); documentary footage and highly theatricalised set-pieces - and actual theatre, and street theatre; song inserts (I just know that Kara Juro's 'Ali Baba' song will be rattling around my head for at least a fortnight - "Bero Bero Bero Bero Bero Bero. . .") and intertitles (which can convey suppressed dialogue, interstitial narration, the date and time in major international cities, or local weather reports).

It's almost a compendium of everything Oshima had done up to that point, with significant nods to important colleagues as well (Yoshida-like radical decentring in some passages, for example, but also strong whiffs of Godard and Pasolini). You never know what to expect. The first shoplifting scene is delivered through hand-held, highly mobile documentary camera work, in amongst the crowds; the second through Violence at Noon-style fragmentary montage. The scene in which Birdey and Umeko spy on Toura through fake rain features a hypnotic series of slow zooms out; the meeting with the sex therapist combines shaky, up-close, hand-held (i.e. 'documentary') footage containing audible camera noise with more distanced, statically-mounted (i.e. 'staged') footage. The whole film wriggles around in a no-man's land between documentary and fiction, but in a completely different way to, say, Imamura's A Man Vanishes. Oshima isn't mixing things up to complicate or explore or expose reality, but is co-opting the real to add some gritty texture to his fictional world, and, in some cases, to provide the most direct route to the ideas he's exploring in his fiction.

The film lurches from set-piece to set-piece, but now I can see the clear (if sometimes arbitrary and dream-like) narrative thread that ties them all together. Some sequences have acquired additional significance for me over time. The sequence in which we eavesdrop on members of Oshima's stock company musing about sex, in scanty available light, used to seem overlong, but as I've become more familiar with some of the key figures (e.g. Toura, Sato and Watanabe) it's become considerably more interesting. I still find the Kara Juro sequence at the end of the film one of the less satisfying ones. Maybe because he's punctuated the film all along it's less surprising than other sequences, or maybe I like to think of the bookshop as the focal location of the movie, and it starts to wind down once the characters leave it behind.

Inferno of First Love

Hani's masterpiece has all of the diversity of the Oshima, but it's marshalled with extreme precision into one of the most masterful and muscular pieces of filmmaking of the 1960s. She and He is a great film, but this is in another league entirely in terms of ambition and achievement. The film ventures into some incredibly dark territory (S&M, incest, pedophilia), but miraculously manages to preserve an extreme tenderness and innocence in the treatment of its central couple.

Personally, I'm completely over incest as a literary device, the creakily predictable deep, dark family secret in any film, play or novel with a deep, dark family secret. It's become so hackneyed as a plot device that it often ceases to have any emotional resonance. Well, not here. The glimpses we get of Shun's stepfather exploiting the boy, even if they're just a stray caress, or a disembodied voice calling out to him, are some of the most distressing scenes I've ever seen: they cut right to the heart of the emotional violence of incest, even if they're not conventionally 'explicit.'

No less disturbing are the scenes in which Shun's potential (or are we just projecting this?) pedophilia is skirted. He has befriended a very young girl, and there is some kind of incident in a graveyard. Hani is ambiguous, as the film's visuals slip into Shun's reverie at the crucial moment, but there's a horribly intense close-up of him clasping her tiny hand that dredges up our dread. Shun is seen, and there is a chase, but we never know for sure just how innocent or guilty (or even conscious) he is of the 'crime.' When he masturbates towards the end of the film, one of the elements flashing through his mind is a grotesque vision of naked boys with old-man masks cavorting through the park - a Terayama touch, no doubt, and maybe even more creepy and vertiginous than the earlier shots.

Nanami's S&M session is a walk in the park compared to Shun's walk in the park. The film has a very careful structure that draws its stylistic diversity together. After two early flashbacks (Shun's story and Nanami's) conveyed in a brilliantly fluid combination of styles (pseudo-documentary footage, post-modern confronting-the-camera inserts, point-of-view shots, artful skewed compositions, stills) that suggests a kind of modern impressionism, the film is built around three 'filmic' or 'filmed' episodes associated with three characters. Shun's hypnosis therapy (after the incident with the girl) takes the amazing cinematic form of a film of his subconscious (visible to those in attendance) projected onto smoke. It proves to be as harrowing as every other of the film's dips into Shun's troubled head, but it's a brilliantly conceived sequence. The subsequent episode devoted to Nanami (which, like Shun's session, expands upon a hidden aspect of her character) is the S&M session she engages in, which is being photographed and filmed for subsequent exploitation. Both of these intense sequences are complemented at the end of the film by Daisuke's actual film, a confessional amateur work about his first love, the viewing of which in some way seems to clear the ground for the central couple to progress their relationship. Unless fate intervenes.

It's a simply fantastic film, dramatically compelling and intellectually rewarding, and I haven't even really got into the amazing, surprising shots that pepper it (the unexplained insert of a dog's head before Shun's hypnosis; the startling series of rapid dissolves that adds the psychological punch to what Nanami views from her window at the end of the film).

Calcutta

Not really in contention for my list, but I watched it, and it's from the right decade, so: lots of good material, but the film seemed to be rather unstructured and consequently kept losing momentum. I haven't watched Phantom India yet, but this really did seem like loosely organised outtakes. The sequences with the lepers were the most compelling, but nobody's going to mistake this for The House Is Black.

It's hard for me to be objective about this film. As the first Japanese New Wave film I saw, it really tore the top of my head off, and it still has a similar effect on me. What I found / find so amazing about it is the sheer profligacy of its technique and the knottiness of its treatment of its subject (sexuality, crime, revolution, performance): "an unsolvable, solvable mystery". Oshima throws everything up on the screen: black and white (classical studio and grungy verite) and colour (with rogue Roeg reds); documentary footage and highly theatricalised set-pieces - and actual theatre, and street theatre; song inserts (I just know that Kara Juro's 'Ali Baba' song will be rattling around my head for at least a fortnight - "Bero Bero Bero Bero Bero Bero. . .") and intertitles (which can convey suppressed dialogue, interstitial narration, the date and time in major international cities, or local weather reports).

It's almost a compendium of everything Oshima had done up to that point, with significant nods to important colleagues as well (Yoshida-like radical decentring in some passages, for example, but also strong whiffs of Godard and Pasolini). You never know what to expect. The first shoplifting scene is delivered through hand-held, highly mobile documentary camera work, in amongst the crowds; the second through Violence at Noon-style fragmentary montage. The scene in which Birdey and Umeko spy on Toura through fake rain features a hypnotic series of slow zooms out; the meeting with the sex therapist combines shaky, up-close, hand-held (i.e. 'documentary') footage containing audible camera noise with more distanced, statically-mounted (i.e. 'staged') footage. The whole film wriggles around in a no-man's land between documentary and fiction, but in a completely different way to, say, Imamura's A Man Vanishes. Oshima isn't mixing things up to complicate or explore or expose reality, but is co-opting the real to add some gritty texture to his fictional world, and, in some cases, to provide the most direct route to the ideas he's exploring in his fiction.

The film lurches from set-piece to set-piece, but now I can see the clear (if sometimes arbitrary and dream-like) narrative thread that ties them all together. Some sequences have acquired additional significance for me over time. The sequence in which we eavesdrop on members of Oshima's stock company musing about sex, in scanty available light, used to seem overlong, but as I've become more familiar with some of the key figures (e.g. Toura, Sato and Watanabe) it's become considerably more interesting. I still find the Kara Juro sequence at the end of the film one of the less satisfying ones. Maybe because he's punctuated the film all along it's less surprising than other sequences, or maybe I like to think of the bookshop as the focal location of the movie, and it starts to wind down once the characters leave it behind.

Inferno of First Love

Hani's masterpiece has all of the diversity of the Oshima, but it's marshalled with extreme precision into one of the most masterful and muscular pieces of filmmaking of the 1960s. She and He is a great film, but this is in another league entirely in terms of ambition and achievement. The film ventures into some incredibly dark territory (S&M, incest, pedophilia), but miraculously manages to preserve an extreme tenderness and innocence in the treatment of its central couple.

Personally, I'm completely over incest as a literary device, the creakily predictable deep, dark family secret in any film, play or novel with a deep, dark family secret. It's become so hackneyed as a plot device that it often ceases to have any emotional resonance. Well, not here. The glimpses we get of Shun's stepfather exploiting the boy, even if they're just a stray caress, or a disembodied voice calling out to him, are some of the most distressing scenes I've ever seen: they cut right to the heart of the emotional violence of incest, even if they're not conventionally 'explicit.'

No less disturbing are the scenes in which Shun's potential (or are we just projecting this?) pedophilia is skirted. He has befriended a very young girl, and there is some kind of incident in a graveyard. Hani is ambiguous, as the film's visuals slip into Shun's reverie at the crucial moment, but there's a horribly intense close-up of him clasping her tiny hand that dredges up our dread. Shun is seen, and there is a chase, but we never know for sure just how innocent or guilty (or even conscious) he is of the 'crime.' When he masturbates towards the end of the film, one of the elements flashing through his mind is a grotesque vision of naked boys with old-man masks cavorting through the park - a Terayama touch, no doubt, and maybe even more creepy and vertiginous than the earlier shots.

Nanami's S&M session is a walk in the park compared to Shun's walk in the park. The film has a very careful structure that draws its stylistic diversity together. After two early flashbacks (Shun's story and Nanami's) conveyed in a brilliantly fluid combination of styles (pseudo-documentary footage, post-modern confronting-the-camera inserts, point-of-view shots, artful skewed compositions, stills) that suggests a kind of modern impressionism, the film is built around three 'filmic' or 'filmed' episodes associated with three characters. Shun's hypnosis therapy (after the incident with the girl) takes the amazing cinematic form of a film of his subconscious (visible to those in attendance) projected onto smoke. It proves to be as harrowing as every other of the film's dips into Shun's troubled head, but it's a brilliantly conceived sequence. The subsequent episode devoted to Nanami (which, like Shun's session, expands upon a hidden aspect of her character) is the S&M session she engages in, which is being photographed and filmed for subsequent exploitation. Both of these intense sequences are complemented at the end of the film by Daisuke's actual film, a confessional amateur work about his first love, the viewing of which in some way seems to clear the ground for the central couple to progress their relationship. Unless fate intervenes.

It's a simply fantastic film, dramatically compelling and intellectually rewarding, and I haven't even really got into the amazing, surprising shots that pepper it (the unexplained insert of a dog's head before Shun's hypnosis; the startling series of rapid dissolves that adds the psychological punch to what Nanami views from her window at the end of the film).

Calcutta

Not really in contention for my list, but I watched it, and it's from the right decade, so: lots of good material, but the film seemed to be rather unstructured and consequently kept losing momentum. I haven't watched Phantom India yet, but this really did seem like loosely organised outtakes. The sequences with the lepers were the most compelling, but nobody's going to mistake this for The House Is Black.

- Steven H

- Joined: Tue Nov 02, 2004 3:30 pm

- Location: NC

Its great to see two of my favorite films getting some attention, Naruse's Her Lonely Lane and Hani's Inferno of First Love. Could two films be any more different?

If you ever want to see something really interesting, Yokoo Tadanori, who played Birdy Hilltop in Diary of a Shinjuku Thief, made some experimental pop art related animated films (which are available at cdjapan). You can also see some of them on YouTube: KISS KISS KISS (1964) and Kachi Kachi Yama (1965). It makes the film that much better to know he's capable of this kind of thing, and it also gives you an insight as to how Oshima used other artists in his films (Adachi Masao in Death by Hanging and student filmmaker Oshima fans in The Man Who Left His Will On Film.)

If you ever want to see something really interesting, Yokoo Tadanori, who played Birdy Hilltop in Diary of a Shinjuku Thief, made some experimental pop art related animated films (which are available at cdjapan). You can also see some of them on YouTube: KISS KISS KISS (1964) and Kachi Kachi Yama (1965). It makes the film that much better to know he's capable of this kind of thing, and it also gives you an insight as to how Oshima used other artists in his films (Adachi Masao in Death by Hanging and student filmmaker Oshima fans in The Man Who Left His Will On Film.)

-

yoshimori

- Joined: Wed Nov 03, 2004 2:03 am

- Location: LA CA

My taste in 60s films (Godard, Antonioni, Fellini, Resnais, Welles, Bresson, Paradjanov, Hitchcock) seems to be pretty canonical, or, maybe better put ... the canon seems to have veered onto the right path for the 60s!

I would recommend a few films not mentioned already and second a couple others:

Two french films blew me away when I saw them at the Cinematheque a decade ago: Thomas, the Impostor (Franju from Cocteau's script; dreamy WWI tale) and Trans-Europ-Express (surgically precise Robbe-Grillet). Of course, there are no available transfers.

I'd "second" the Hani Inferno recs above. This is my probably 3rd favorite film of 1968, after 2001 and Petulia.

I'm not a big Polanski fan, but always found his Cul-de-sac to be hilarious. r2uk-able.

I'm afraid Fellini's Satyricon, 1969, will be neglected. A masterpiece of costume and production design and of extras casting.

1969 also yielded, besides Z and Passion of Anna and the like, two more great Japanese films: Funeral Procession of Roses (Matsumoto, available r2jp) and Shonen [Boy] (oop from japnewwaveclassics).

I would recommend a few films not mentioned already and second a couple others:

Two french films blew me away when I saw them at the Cinematheque a decade ago: Thomas, the Impostor (Franju from Cocteau's script; dreamy WWI tale) and Trans-Europ-Express (surgically precise Robbe-Grillet). Of course, there are no available transfers.

I'd "second" the Hani Inferno recs above. This is my probably 3rd favorite film of 1968, after 2001 and Petulia.

I'm not a big Polanski fan, but always found his Cul-de-sac to be hilarious. r2uk-able.

I'm afraid Fellini's Satyricon, 1969, will be neglected. A masterpiece of costume and production design and of extras casting.

1969 also yielded, besides Z and Passion of Anna and the like, two more great Japanese films: Funeral Procession of Roses (Matsumoto, available r2jp) and Shonen [Boy] (oop from japnewwaveclassics).

- Michael

- Joined: Wed Nov 03, 2004 12:09 pm

- zedz

- Joined: Sun Nov 07, 2004 7:24 pm

I don't think Paradzhanov is quite in the canon (yet), but Colour of Pomegranates is likely to top my list, even though I'm unlikely to see it again before close of voting, in the absence of a decent DVD.yoshimori wrote:My taste in 60s films (Godard, Antonioni, Fellini, Resnais, Welles, Bresson, Paradjanov, Hitchcock) seems to be pretty canonical, or, maybe better put ... the canon seems to have veered onto the right path for the 60s!

I think you're right about the 60s canon. It's hard to quibble with those directors (though there are plenty of their 60s films with which I'd gladly quibble), even if there's a wealth of lesser known filmmakers doing work just as good or better.

This has been bumped well down my list thanks to recent arrivals, but it's by far my favourite Fellini of the decade and I'd be pleased to see it get some attention. People should definitely see it before they catch Paranoid Park, just so they can appreciate how flexible Rota's score can be.Michael wrote:Juliet of the Spirits deserves to be mentioned also.

- Steven H

- Joined: Tue Nov 02, 2004 3:30 pm

- Location: NC

One of my favorite filmmakers of this decade is Okamoto Kihachi, who embodied so many wonderful things about film being a technical master and unique visionary who combined dark humor, war, drama, music, unforgettable character actors, and tenacious editing rhythms to form what became to be known as the Kihachi Spirit! Those who weathered the multi-colored subtitles on the Japan's Longest Day disc became a little bit closer to the man last year thanks to AnimEigo, and hopefully there will be more of that to come in Nov. with Battle of Okinawa. I've gone on and on elsewhere about the brilliance of his earlier comedies (resembling Wilder in The Apartment and maybe Double Indemnity, Germi, early Godard, some say Aldrich) and war films (late DeToth and Mann, all Fuller but spunkier) and of course his samurai stuff. Adventurous, artful entertainment with biting social commentary, and funny as hell to boot.

I'm having issues not putting almost every 60s film I've seen of his on this list (almost because Red Lion and the Zatoichi flick didn't do much for me, especially after something like Age of Assassins.) Even (maybe especially) his truly bizarre Noh musical war satire (seriously) which made almost no money on release (never an indicator of quality, to be sure) is poised to dip its feet in the top 50 pond. Speaking of Age of Assassins, as of now, Oct. whatever 2007, my avatar is Reiko Dan from Age of Assassins, looking mighty sultry, in what might be one of the best entrances in spy film history (even if it's a *mock* spy film.) Needless to say, Nakadai falls for her, or fumbles at least (he's a goof in that flick.)

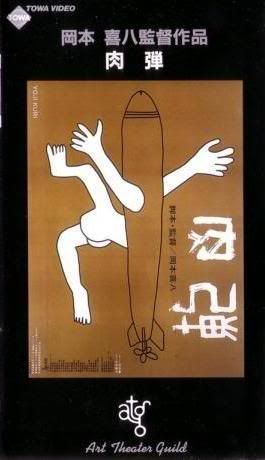

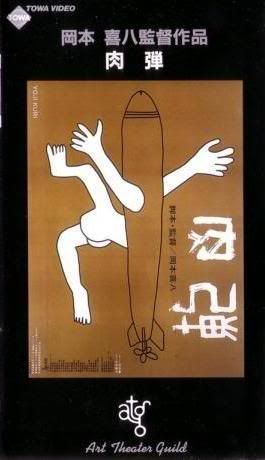

What *really* takes the cake, however, is his ATG films, Human Bullet (i.e. Suicide Phallus, I'm kidding, but Nikudan is also a play on words like "cock" in english) being the film he tried desperately to get made at Toho but had to go elsewhere (his other ATG stuff in the 70s is also more than worthwhile). As of now this is MIA in english subtitled land (even the underground folks), but lo and behold it seems somebody is working on this because the first six minutes are up at a friend's french film blog wildgrounds.com, and I want everyone to check it out (its like reading the first few pages of a book that you KNOW is going to be good.) I think Geneon would be the go to people since they seem to have control of the ATG catalog, but who knows since all the films had multiple productions co.s investing, video rights are surely a swampy arena (but who cares, somebody just put it out already Criterion? MoC? Yume? Geneon? SecondRun? Kino? Wild Side? Bfi? I don't care). How can a film be even remotely mediocre with an original poster (well, VHS cover art, but its the original poster I swear) like this:

I'm having issues not putting almost every 60s film I've seen of his on this list (almost because Red Lion and the Zatoichi flick didn't do much for me, especially after something like Age of Assassins.) Even (maybe especially) his truly bizarre Noh musical war satire (seriously) which made almost no money on release (never an indicator of quality, to be sure) is poised to dip its feet in the top 50 pond. Speaking of Age of Assassins, as of now, Oct. whatever 2007, my avatar is Reiko Dan from Age of Assassins, looking mighty sultry, in what might be one of the best entrances in spy film history (even if it's a *mock* spy film.) Needless to say, Nakadai falls for her, or fumbles at least (he's a goof in that flick.)

What *really* takes the cake, however, is his ATG films, Human Bullet (i.e. Suicide Phallus, I'm kidding, but Nikudan is also a play on words like "cock" in english) being the film he tried desperately to get made at Toho but had to go elsewhere (his other ATG stuff in the 70s is also more than worthwhile). As of now this is MIA in english subtitled land (even the underground folks), but lo and behold it seems somebody is working on this because the first six minutes are up at a friend's french film blog wildgrounds.com, and I want everyone to check it out (its like reading the first few pages of a book that you KNOW is going to be good.) I think Geneon would be the go to people since they seem to have control of the ATG catalog, but who knows since all the films had multiple productions co.s investing, video rights are surely a swampy arena (but who cares, somebody just put it out already Criterion? MoC? Yume? Geneon? SecondRun? Kino? Wild Side? Bfi? I don't care). How can a film be even remotely mediocre with an original poster (well, VHS cover art, but its the original poster I swear) like this:

- zedz

- Joined: Sun Nov 07, 2004 7:24 pm

The Testament of Orpheus

How could you not love this film? One of the most enchanting pieces of pure solipsism ever materialised on a cinema screen (it's hard to believe that this was conventionally filmed with a big old clunky movie camera). Cocteau's visual effects are spectacularly conceived and elegantly executed, yet brilliantly simple (mostly variations on reverse motion, dissolves and overcranking), his eye for startling settings acute, and his content more esoteric and personal than ever. It's utterly beguiling and, once you cotton on to the conceit (Cocteau, at the end of his life, bids farewell to the ideas, characters, places and people that were most important to him), very moving.

The Profound Desire of the Gods

It looks like I forgot to comment on this when I watched it a short time back. The first time I saw this was in an anamorphic 16mm print, projected without an anamorphic lens (i.e. with added Sokhurov scrunching). Needless to say, the JNWC disc offered a better viewing experience, but even in compromised form the film completely sucked me in.

Imamura's 60s body of work is much more stylistically and thematically consistent than Oshima's, with each feature from The Insect Woman (allowing for the brilliant sidestep of A Man Vanishes) methodically exploring further possibilities of widescreen composition (in a rather more classical mode than such fellow travellers as Yoshida) and building on a well-defined set of concerns, e.g. women in society, class divisions, sex and incest (an Imamura film without incest would be like a Kubrick film without gurning) - exploitation is the unifying idea.

The Profound Desire of the Gods, in glorious colour, is the last in the series (to be rudely interrupted by the commercial failure of the film), and wraps everything up in a spectacular three-hour bundle. It's an ethnographic, absurdist epic full of dark corners that push you away while luring you forward. The character relations take a while to fathom (and are often off-putting once you do), but the verve of the storytelling relentlessly draws the viewer into the community's web of self-interest and resentment.

If there's such a thing as a genre of Asian "island" films, this film surely occupies a central position in that genre. Before it, we had the melancholy Twenty-four Eyes and The Naked Island; films that followed its example, like Yanagimachi's Fire Festival, Park's To the Starry Island, and even Kim's The Isle, would be much harder-edged and more critically engaged.

The prospect of seeing this film in a forthcoming Eclipse set is heartening, though it more than warrants the serious contextualisation a 'proper' Criterion release could afford.

How could you not love this film? One of the most enchanting pieces of pure solipsism ever materialised on a cinema screen (it's hard to believe that this was conventionally filmed with a big old clunky movie camera). Cocteau's visual effects are spectacularly conceived and elegantly executed, yet brilliantly simple (mostly variations on reverse motion, dissolves and overcranking), his eye for startling settings acute, and his content more esoteric and personal than ever. It's utterly beguiling and, once you cotton on to the conceit (Cocteau, at the end of his life, bids farewell to the ideas, characters, places and people that were most important to him), very moving.

The Profound Desire of the Gods

It looks like I forgot to comment on this when I watched it a short time back. The first time I saw this was in an anamorphic 16mm print, projected without an anamorphic lens (i.e. with added Sokhurov scrunching). Needless to say, the JNWC disc offered a better viewing experience, but even in compromised form the film completely sucked me in.

Imamura's 60s body of work is much more stylistically and thematically consistent than Oshima's, with each feature from The Insect Woman (allowing for the brilliant sidestep of A Man Vanishes) methodically exploring further possibilities of widescreen composition (in a rather more classical mode than such fellow travellers as Yoshida) and building on a well-defined set of concerns, e.g. women in society, class divisions, sex and incest (an Imamura film without incest would be like a Kubrick film without gurning) - exploitation is the unifying idea.

The Profound Desire of the Gods, in glorious colour, is the last in the series (to be rudely interrupted by the commercial failure of the film), and wraps everything up in a spectacular three-hour bundle. It's an ethnographic, absurdist epic full of dark corners that push you away while luring you forward. The character relations take a while to fathom (and are often off-putting once you do), but the verve of the storytelling relentlessly draws the viewer into the community's web of self-interest and resentment.

If there's such a thing as a genre of Asian "island" films, this film surely occupies a central position in that genre. Before it, we had the melancholy Twenty-four Eyes and The Naked Island; films that followed its example, like Yanagimachi's Fire Festival, Park's To the Starry Island, and even Kim's The Isle, would be much harder-edged and more critically engaged.

The prospect of seeing this film in a forthcoming Eclipse set is heartening, though it more than warrants the serious contextualisation a 'proper' Criterion release could afford.

- zedz

- Joined: Sun Nov 07, 2004 7:24 pm

The Vanishing Corporal

Hardly great Renoir, but a very good film nevertheless. Comparatively straight in its style (at least, compared with The Testament of Dr. Cordelier and Le Petit Theatre de Jean Renoir), but characteristically Renoiresque in its themes and generosity of characterisation.

A Man Vanishes

An extremely impressive film. The second viewing was necessarily lacking the brutal trapdoor shock of the first, but on the other hand it gained in fascination knowing what was coming. The film starts out in impeccable documentary mode as the exploration of the life and circumstances of one of the many ‘missing men' prevalent in Japan at the time (see also Woman of the Dunes). For the first hour, it's an involving enough tour of friends and family, with some mild speculation as to why Mr Oshima disappeared. In the second hour, the film comes to much more closely resemble a serious investigation, as secrets are uncovered, speculations about foul play are aired (as in a particularly intense session with a psychic) and contradictory witnesses come head to head.

The form of the documentary (which has been somewhat peculiar all along, with sound and image running parallel rather than completely in sync) also starts to buckle and bend, as the filmmakers themselves become inveigled in the story (Oshima's fiancee starts to transfer her affections to the interviewer) and odd stylistic incursions seem to bubble up from the film's subconscious (flash-frame flash-forward glimpses of an ominous ritual, for example). This section ends up in a highly charged confrontation between a fishmonger and the fiancee's sister, whom the former claims to have seen with the missing man on several occasions for which she cannot account. The scene grinds on into a fraught stalemate until Imamura breaks the spell with his coup de grace. The remaining twenty minutes of the film pick up the pieces.

I can't say too much more, but this is a one-of-a-kind film I highly recommend.

The Hustler

Another fine, mature early 60s Hollywood film. I wonder whether, in some parallel universe in which ‘New Hollywood' never happened at the end of the sixties, old Hollywood might have grown up all on its own. Amongst the mediocre, bloated musicals, failing epics and lame comedies, there were distinct signs of increasing maturity of subject matter, complexity of tone and technical experimentation in such early 60s films as this one, Psycho, The Apartment and The Manchurian Candidate, even though the architects were such venerable old hands as Hitchcock, Wilder, and Alexander Trauner. Nearly 50 years after he entered the industry, James Wong Howe was creating some of the most radical cinematography of 1966 (hardly a staid years for cinema) in Seconds. Peel away the awful dross of Hollywood in those years, and there's a vital forward-looking cinema buried beneath (and, hey, it's not as if the dross ended in 1970).

Robert Rossen is no slouch, but it's Eugene Schufftan who's the hero of The Hustler for me, bringing the incredible weight of his experience to bear on fresh subject matter. The ‘maturity' of the material is somewhat stage-soiled (but no less valid for that) and there are still the awkward compromises demanded by censorship, but Schufftan turns it into compelling cinema.

Signs of Life

Always an invigorating watch, and maybe it's Herzog's best feature. It's just visually gorgeous, with superb capturing of textures and space (as is often the case, he's got an amazing location to work with), and it's emotionally moving without being dramatically overloaded – the emotion is often subsumed within the visuals, as with the sad and beautiful daytime fireworks display, or the extreme, extreme longshots of an ant-like Stroszek scurrying around the fortifications. Plus, it's got an exquisite score. Even before Popol Vuh (but not, strictly speaking, before Florian Fricke), Herzog had a fantastic instinct for the right music, and he can create startlingly right audio-visual blends out of rather unlikely matches (e.g. Leonard Cohen in Fata Morgana).

Hardly great Renoir, but a very good film nevertheless. Comparatively straight in its style (at least, compared with The Testament of Dr. Cordelier and Le Petit Theatre de Jean Renoir), but characteristically Renoiresque in its themes and generosity of characterisation.

A Man Vanishes

An extremely impressive film. The second viewing was necessarily lacking the brutal trapdoor shock of the first, but on the other hand it gained in fascination knowing what was coming. The film starts out in impeccable documentary mode as the exploration of the life and circumstances of one of the many ‘missing men' prevalent in Japan at the time (see also Woman of the Dunes). For the first hour, it's an involving enough tour of friends and family, with some mild speculation as to why Mr Oshima disappeared. In the second hour, the film comes to much more closely resemble a serious investigation, as secrets are uncovered, speculations about foul play are aired (as in a particularly intense session with a psychic) and contradictory witnesses come head to head.

The form of the documentary (which has been somewhat peculiar all along, with sound and image running parallel rather than completely in sync) also starts to buckle and bend, as the filmmakers themselves become inveigled in the story (Oshima's fiancee starts to transfer her affections to the interviewer) and odd stylistic incursions seem to bubble up from the film's subconscious (flash-frame flash-forward glimpses of an ominous ritual, for example). This section ends up in a highly charged confrontation between a fishmonger and the fiancee's sister, whom the former claims to have seen with the missing man on several occasions for which she cannot account. The scene grinds on into a fraught stalemate until Imamura breaks the spell with his coup de grace. The remaining twenty minutes of the film pick up the pieces.

I can't say too much more, but this is a one-of-a-kind film I highly recommend.

The Hustler

Another fine, mature early 60s Hollywood film. I wonder whether, in some parallel universe in which ‘New Hollywood' never happened at the end of the sixties, old Hollywood might have grown up all on its own. Amongst the mediocre, bloated musicals, failing epics and lame comedies, there were distinct signs of increasing maturity of subject matter, complexity of tone and technical experimentation in such early 60s films as this one, Psycho, The Apartment and The Manchurian Candidate, even though the architects were such venerable old hands as Hitchcock, Wilder, and Alexander Trauner. Nearly 50 years after he entered the industry, James Wong Howe was creating some of the most radical cinematography of 1966 (hardly a staid years for cinema) in Seconds. Peel away the awful dross of Hollywood in those years, and there's a vital forward-looking cinema buried beneath (and, hey, it's not as if the dross ended in 1970).

Robert Rossen is no slouch, but it's Eugene Schufftan who's the hero of The Hustler for me, bringing the incredible weight of his experience to bear on fresh subject matter. The ‘maturity' of the material is somewhat stage-soiled (but no less valid for that) and there are still the awkward compromises demanded by censorship, but Schufftan turns it into compelling cinema.

Signs of Life

Always an invigorating watch, and maybe it's Herzog's best feature. It's just visually gorgeous, with superb capturing of textures and space (as is often the case, he's got an amazing location to work with), and it's emotionally moving without being dramatically overloaded – the emotion is often subsumed within the visuals, as with the sad and beautiful daytime fireworks display, or the extreme, extreme longshots of an ant-like Stroszek scurrying around the fortifications. Plus, it's got an exquisite score. Even before Popol Vuh (but not, strictly speaking, before Florian Fricke), Herzog had a fantastic instinct for the right music, and he can create startlingly right audio-visual blends out of rather unlikely matches (e.g. Leonard Cohen in Fata Morgana).

- zedz

- Joined: Sun Nov 07, 2004 7:24 pm

Two weeks to go, and I've finally got through the Oshimas:

Boy

The last Oshima of the sixties had previously been nudged out of my list, but seeing it again has probably nudged it back in. Stylistically, it's a much more ‘classical' (or at least moderated) film than many of the ones that preceded it: it's basically linear and all pretty much takes place within a single level of fictional reality, for instance. Nevertheless, it serves as yet another example of Oshima's formal range, with the dominant filmic unit this time being single-shot, fixed-position phrases, with extremely enthusiastic, though sub-Yoshida, placement of action on the frame edges.

In terms of subject matter, the film is as tough as anything else he did at the time. The ‘Boy' of the title is a child exploited in the most ghastly way by his parents, having to hurl himself in front of passing cars so they can extort money from the drivers. It actually harks back to The Sun's Burial in its pointed sordidness and the implication of all of Japanese society in the critique. Not only do the titles run over converted / subverted Japanese flags, the rising sun become a black hole, but Oshima smuggles the flag into the background of scene after scene. Just look at how a Japanese flag appears somewhere in practically every shot that comprises the first motoring-accident sequence, or how that ominous red circle can be faintly made out behind textured glass in the family's apartment about halfway through.

The film explores several modes, from family drama to first-person reverie (in many cases we share the boy's limited or distorted perception of what's going on, and his passive equanimity is what gives the film its huge emotional punch) to semi-documentary. Like many of Oshima's films, it seems to be riffing on actual events, but in an imaginatively radicalised way that goes way beyond neo-realism. Fantastic modernist score as well.

This was the film that first got Oshima serious recognition in the west, and it remains a superb entry point to his challenging, exhilarating body of work. It should also caution us about assuming we know what's going on with film: even at a time in which western eyes were arguably most attentive to world cinema, those amazing preceding works were overlooked.

Boy

The last Oshima of the sixties had previously been nudged out of my list, but seeing it again has probably nudged it back in. Stylistically, it's a much more ‘classical' (or at least moderated) film than many of the ones that preceded it: it's basically linear and all pretty much takes place within a single level of fictional reality, for instance. Nevertheless, it serves as yet another example of Oshima's formal range, with the dominant filmic unit this time being single-shot, fixed-position phrases, with extremely enthusiastic, though sub-Yoshida, placement of action on the frame edges.

In terms of subject matter, the film is as tough as anything else he did at the time. The ‘Boy' of the title is a child exploited in the most ghastly way by his parents, having to hurl himself in front of passing cars so they can extort money from the drivers. It actually harks back to The Sun's Burial in its pointed sordidness and the implication of all of Japanese society in the critique. Not only do the titles run over converted / subverted Japanese flags, the rising sun become a black hole, but Oshima smuggles the flag into the background of scene after scene. Just look at how a Japanese flag appears somewhere in practically every shot that comprises the first motoring-accident sequence, or how that ominous red circle can be faintly made out behind textured glass in the family's apartment about halfway through.

The film explores several modes, from family drama to first-person reverie (in many cases we share the boy's limited or distorted perception of what's going on, and his passive equanimity is what gives the film its huge emotional punch) to semi-documentary. Like many of Oshima's films, it seems to be riffing on actual events, but in an imaginatively radicalised way that goes way beyond neo-realism. Fantastic modernist score as well.

This was the film that first got Oshima serious recognition in the west, and it remains a superb entry point to his challenging, exhilarating body of work. It should also caution us about assuming we know what's going on with film: even at a time in which western eyes were arguably most attentive to world cinema, those amazing preceding works were overlooked.

- Awesome Welles

- Joined: Fri Apr 27, 2007 6:02 am

- Location: London

Not a recent viewing but I'd like to write a little something about Memories of Underdevelopment (Alea, 1968). I saw the film a year or so ago on a ropey old VHS copy, it has been released in Brazil, I've not taken the plunge due to pricey postage costs. However I have just found an ebay seller who sells the disc for very cheap (which prompts me to mention the film). For those who are wanting to see this film it can be found here.

Sergio, the protagonist of the film, decides to stay in Cuba after his family and wife move to the US after the Bay of Pigs invasion. He is the symbol of decadence, much like a dead bird which he finds in his cage, he drops this bird off the balcony symbolising his separation from his wife (the free, remaining bird). He thinks of himself as European and that Cuba is an underdeveloped nation. The film follows his musings on politics and culture as he womanises.

Played out in a nonlinear narrative we see, with documentary footage, the events of Revolutionary Cuba, the film succeeds in not being propagandistic. Very much influenced by Italian Neo-Realism and the French New Wave, Alea's film has all the spirit and poingnency of those periods of cinema. The film was also influenced by Revolutionary Soviet Montage, the film makes use of accelerated montage in the periods of documentary reflection, one could perhaps interpret this as a comment on those old times using a dated cinematic device as Alea savours the future with long takes and hand held camera of the forward thinking French New Wave.

Reviews; Guardian, NYTimes, Senses of Cinema.

Sergio, the protagonist of the film, decides to stay in Cuba after his family and wife move to the US after the Bay of Pigs invasion. He is the symbol of decadence, much like a dead bird which he finds in his cage, he drops this bird off the balcony symbolising his separation from his wife (the free, remaining bird). He thinks of himself as European and that Cuba is an underdeveloped nation. The film follows his musings on politics and culture as he womanises.

Played out in a nonlinear narrative we see, with documentary footage, the events of Revolutionary Cuba, the film succeeds in not being propagandistic. Very much influenced by Italian Neo-Realism and the French New Wave, Alea's film has all the spirit and poingnency of those periods of cinema. The film was also influenced by Revolutionary Soviet Montage, the film makes use of accelerated montage in the periods of documentary reflection, one could perhaps interpret this as a comment on those old times using a dated cinematic device as Alea savours the future with long takes and hand held camera of the forward thinking French New Wave.

Reviews; Guardian, NYTimes, Senses of Cinema.

- Dylan

- Joined: Tue Nov 02, 2004 9:28 pm

Here's what I've seen so far for the list's project (from what I can recall):

Last Summer- I wrote about this at length in its own thread. It's a great Evan Hunter novel that Frank Perry did a fine job translating into film. Barbara Hershey's character fascinates me, and the central metaphor is terrific in that clear Of Mice and Men fashion. Should definitely be lifted out of obscurity.

The Collector- An interesting, efficiently executed and often surprising thriller with terrific performances from Terence Stamp and Samantha Eggar.

Three- It's nice to watch Sam Waterston and Charlotte Rampling so young, and so good, but this American attempt at expressing loneliness by the means of, primarily, atmosphere and location is ultimately not very memorable. I'm apparently one of a very small number of people who has actually seen it, though.

The Swimmer- As a short story, it's an amazing piece of work...as a film, we have perfect casting, nice photography and a semi-nostalgic Mantovani-esque Marvin Hamlisch score. But damn, that slow-motion montage is one of the cheesiest things I've ever seen - it took me right out of the film. But everything else is well done. I'd recommend reading the John Cheever story over the feature, but the feature does get almost everything right in its translation. I was surprised to read that my favorite scene in the film wasn't directed by Frank Perry, but Sidney Pollack.

Les Biches- I loved and was completely enamored by the two female leads (particularly their bonding in the opening half hour), and the final scene was incredibly suspenseful. I really enjoy Chabrol's unique brand of thriller.

La Collectionuse- Rohmer is rarely noted for making films with beautiful cinematography (particularly from the eighties onward), but this film, shot by Nestor Almendros, is one of the greatest examples of 1.33:1 color photography I'm aware of. Every shot is beautiful, and to me it looks every bit as great as Days of Heaven, if not better. As for most of Rohmer, the characters are intelligent and engaging, the writing consistently and brilliantly perceptive, and the atmosphere very calm and almost chilling. I really liked the ending.

Suzanne's Career- A terrific and very well-written and acted short subject. Better than the other early New Wave shorts I've seen by Rohmer's peers.

The Sandpiper- Beautifully-written love story with Liz Taylor and Richard Burton at the very height of their powers. The beach atmosphere is hypnotic and lovely, the 2.35:1 color photography perfect and Johnny Mandel's classic melody-driven score tops it off. I wish more Hollywood films these days were even close to this in terms of sophistication and writing.

Never on Sunday- It's enjoyably fluffy for the first hour, then it takes a nose dive in the last few minutes, dropping every potentially dramatic plot point in mid air, ending the story as quickly and as unchallenging and 'nice' as possible. Given the plot and the talent involved, it should've been much better, even as fluff. I do love the title song, though (as an aside: the best recording is by Connie Francis, who also sang it at the 1961 Oscar ceremony), and there are some good lines here and there.

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg- Nothing short of a cinematic dream. I just love it everytime I discover a "new" (that is, previously unseen by me) old European masterpiece. The way the music was affecting me all throughout the piece was unbelievable - I was consistently astonished and artistically inspired by the atmosphere, the colors, the characters, the tempo and energy...and I wasn't expecting the story to be so heartbreaking. I'm happy that after years of being a devotee of art house cinema I've finally caught up with this. Hands down one of the truly greatest films of the '60s.

Last Summer- I wrote about this at length in its own thread. It's a great Evan Hunter novel that Frank Perry did a fine job translating into film. Barbara Hershey's character fascinates me, and the central metaphor is terrific in that clear Of Mice and Men fashion. Should definitely be lifted out of obscurity.

The Collector- An interesting, efficiently executed and often surprising thriller with terrific performances from Terence Stamp and Samantha Eggar.

Three- It's nice to watch Sam Waterston and Charlotte Rampling so young, and so good, but this American attempt at expressing loneliness by the means of, primarily, atmosphere and location is ultimately not very memorable. I'm apparently one of a very small number of people who has actually seen it, though.

The Swimmer- As a short story, it's an amazing piece of work...as a film, we have perfect casting, nice photography and a semi-nostalgic Mantovani-esque Marvin Hamlisch score. But damn, that slow-motion montage is one of the cheesiest things I've ever seen - it took me right out of the film. But everything else is well done. I'd recommend reading the John Cheever story over the feature, but the feature does get almost everything right in its translation. I was surprised to read that my favorite scene in the film wasn't directed by Frank Perry, but Sidney Pollack.

Les Biches- I loved and was completely enamored by the two female leads (particularly their bonding in the opening half hour), and the final scene was incredibly suspenseful. I really enjoy Chabrol's unique brand of thriller.

La Collectionuse- Rohmer is rarely noted for making films with beautiful cinematography (particularly from the eighties onward), but this film, shot by Nestor Almendros, is one of the greatest examples of 1.33:1 color photography I'm aware of. Every shot is beautiful, and to me it looks every bit as great as Days of Heaven, if not better. As for most of Rohmer, the characters are intelligent and engaging, the writing consistently and brilliantly perceptive, and the atmosphere very calm and almost chilling. I really liked the ending.

Suzanne's Career- A terrific and very well-written and acted short subject. Better than the other early New Wave shorts I've seen by Rohmer's peers.

The Sandpiper- Beautifully-written love story with Liz Taylor and Richard Burton at the very height of their powers. The beach atmosphere is hypnotic and lovely, the 2.35:1 color photography perfect and Johnny Mandel's classic melody-driven score tops it off. I wish more Hollywood films these days were even close to this in terms of sophistication and writing.

Never on Sunday- It's enjoyably fluffy for the first hour, then it takes a nose dive in the last few minutes, dropping every potentially dramatic plot point in mid air, ending the story as quickly and as unchallenging and 'nice' as possible. Given the plot and the talent involved, it should've been much better, even as fluff. I do love the title song, though (as an aside: the best recording is by Connie Francis, who also sang it at the 1961 Oscar ceremony), and there are some good lines here and there.